Beset by immigration upheavals and enhanced support for unorthodox populist parties, euro members are relying on loose monetary and tight fiscal policy to generate recovery, cut unemployment and restore faith in European integration: a difficult-to-achieve combination.

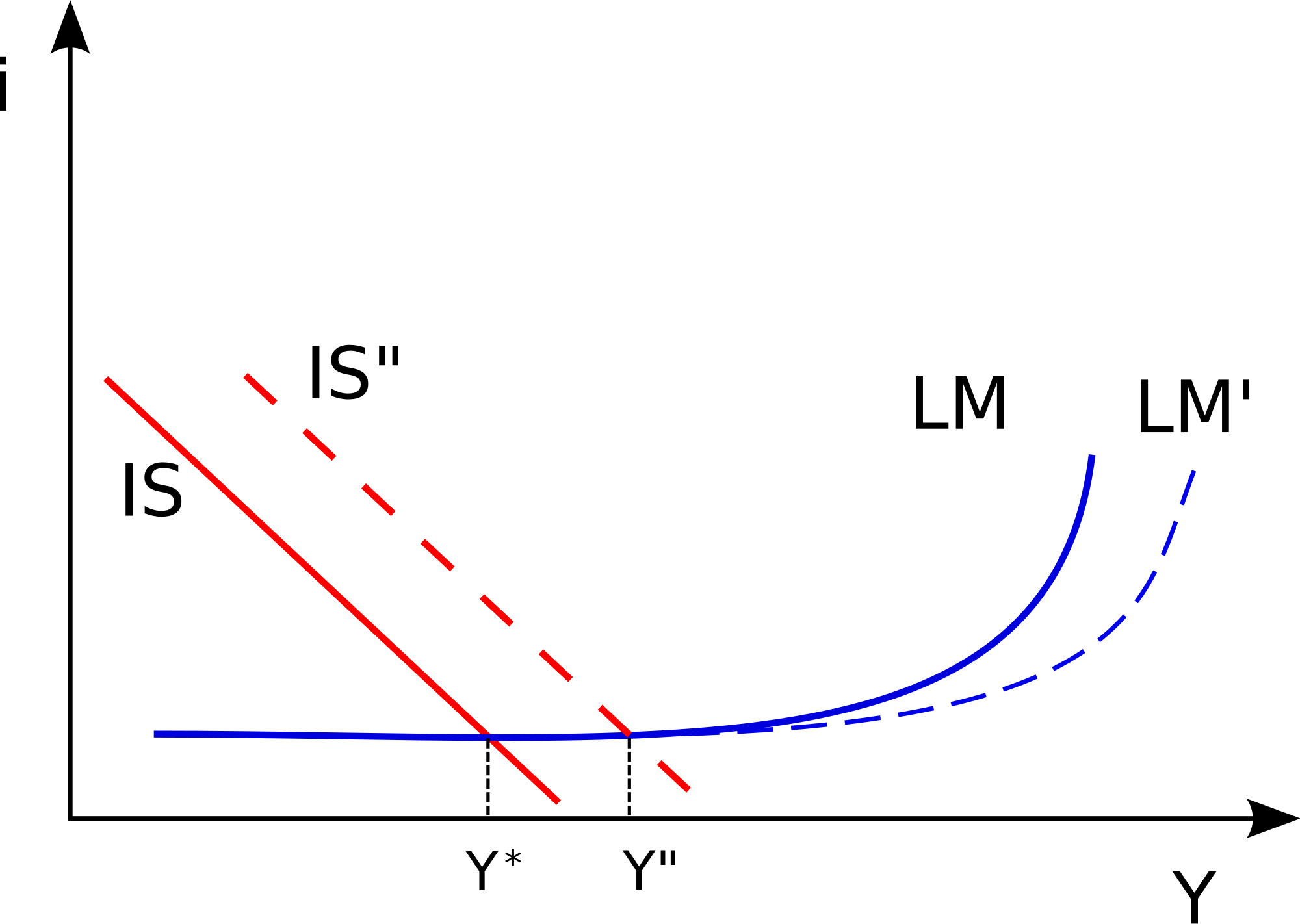

Rather than persist with an approach that risks failure, Draghi and Schäuble, the continent’s two most senior economic policy-makers, should engineer tighter euro-wide monetary policy and simultaneously loosen fiscally. Reining back controversial plans for more ECB government bond asset purchases (quantitative easing) could be balanced by more pragmatic interpretation of euro bloc budgetary objectives, recognising that many southern states are already struggling to meet fiscal goals.

Abandoning further ECB easing could strengthen the euro, countering the ECB’s aspirations for currency weakness and producing unwelcome economic tightening. So the accord would have to embody concomitant fiscal easing, posing problems for the ECB’s independence. Personifying German commitment to economic rigour, Schäuble would need to support the two components of the package, which would be in line with the precepts of the International Monetary Fund.

This more realistic arrangement would meet resistance from budgetary hard-liners arguing EU government debt is out of control. Figures such as Jens Weidmann, the Bundesbank president, would need to be persuaded that the deal represents a satisfactory way of heading off further QE, long opposed by Germany.

In seeking an escape from what its critics term a monetary trap, the ECB faces near-intractable dilemmas. Draghi has been preparing the financial markets for fresh easing when the ECB governing council next makes monetary decisions on 10 March. Yet all the possibilities – increasing the ECB’s €60bn monthly asset purchases, cutting the deposit rate below the current negative 0.3% or widening the range of acquired securities – are opposed by a powerful minority of central bankers on the council.

Further negative interest rate cuts would weaken the profitability of European banks and might undermine the ECB’s obligations to stabilise the banking system. This is a classic conflict between the monetary and financial stability parts of an ECB mandate that has widened since the financial crisis.

For more than two years, inflation has been well below the ECB’s target of just beneath 2%. Yet the zeal with which the ECB president has been promulgating the bank’s desire to meet the target considerably outstrips its ability to do so. Many observers overlook that, although EU treaties enjoin the bank to promote ‘price stability’, the ECB defines what this means in practice. When the ECB was established in 1998, it interpreted its mandate as generating annual inflation of below 2% over the medium term. In response to worries that this might turn out to be deflationary, the ECB in May 2003 redefined the mandate as an inflation rate ‘below, but close to, 2%’.

The religious-like fervour often applied to the mandate by Draghi and Peter Praet, his influential chief economist, is thus somewhat misplaced. The ECB’s guiding parameters are set not by some God-like authority, but by the ECB itself. In the words of the Bible, ‘The ECB giveth and the ECB taketh away.’ Amending the 2003 decision, and restoring the ECB’s own 1998 interpretation of its price stability goal, would require complex deliberations but would allow the bank, without further ado, to meet its statutory mandate.

Draghi himself signalled one route to compromise when, in a speech on 4 February, he outlined (and rejected) the view of some central bankers that the ECB does not need to be ‘overly responsive’ to short-term oil price-induced inflation fluctuations. Draghi cited such critics as saying, ‘We can simply redefine the medium-term horizon over which price stability is maintained and “wait it out” until inflation returns to our objective.’

Another sign of the ECB’s complicated balancing act came on 8 February with a joint Franco-German newspaper article by Weidmann and François Villeroy de Galhau, governor of the Banque de France, calling for more European integration. The German text spoke of eventually setting up a euro area ‘finance ministry’ that would help restore the balance between ‘liability and control’. The French version referred to a ‘treasury’ that would balance ‘responsibility and control’. Weidmann clarified his remarks after publication, saying that the oft-cited euro finance ministry idea was a theoretical option, not realisable for the time being.